In a world full of CNC routers, cordless brad nailers, and laser sited chop saws, it might seem odd, even unnecessary, to reach for a hand saw and a chisel. But many of us do. We plane our boards flat with muscle, sweat and intention. We mark our dovetails with knife and gauge. We reach for the familiar weight of a wooden mallet instead of plugging in a router (my most disliked modern power tool).

Why?

Because there is something deeply satisfying in working with our hands, unaided by machinery. There’s rhythm in a well set plane. There’s joy in the resistance and scent of wood fibers giving way under a sharp chisel. There’s mindfulness in every step. For many of us, traditional hand tool woodworking is a way to slow down, connect to material, and rediscover what it means to truly make something. The hours I spend in my shop are some of my most peaceful and satisfying.

The Problem of Gatekeeping in Woodworking

Unfortunately, with tradition sometimes comes exclusivity. There’s a tendency (Specifically on woodworking forums, in person and even YouTube) in the woodworking community, as in many crafts, to slip into gatekeeping. You’re not “serious” unless you use hide glue. You’re not a real woodworker unless you cut your dovetails by hand. If you didn’t sharpen your plane iron on a hard Arkansas stone by candlelight, well… maybe you’re not doing it right etc.

Let’s stop that.

Let’s be mindful and inclusive of people’s creative needs and methods. There’s room in this wonderful hobby/pastime/profession/passion for everyone. I believe, every person has something they can teach (although it may or may not be woodworking related).

Woodworking is for everyone.

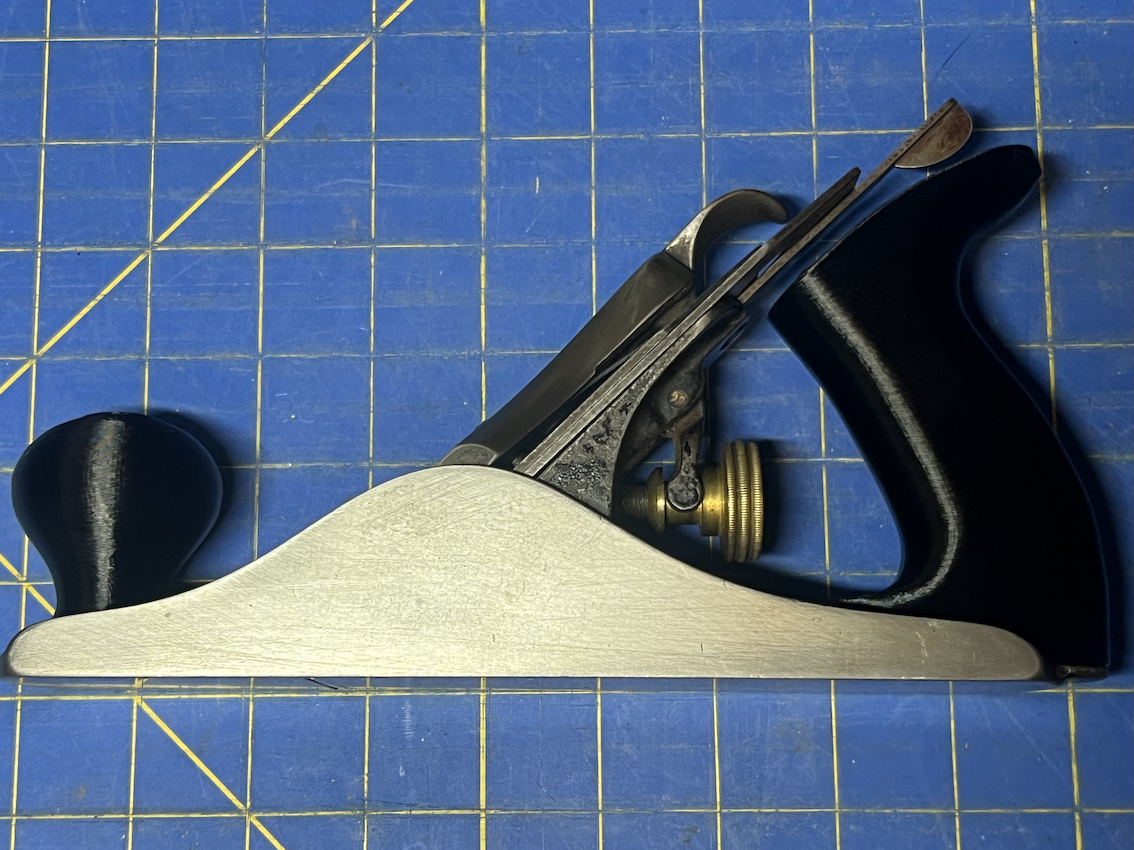

Whether you’re working out of a converted garage with a full wall of Festool or you’ve got a folding table and a Stanley No. 4 from a flea market, you’re a woodworker. Whether you make shaker cabinets, Maloof chairs, or cosplay armor, you’re a maker. Gatekeeping has no place in a community that should be built on curiosity, support, and shared joy.

The Woodwrigh’s School

Roy Underhill, the iconic host of The Woodwright’s Shop, asked students, via the school’s website, not to arrive at his Woodwright’s School in Pittsboro, NC (now sadly closed) wearing logoed T-shirts, but instead to wear button-down shirts. At first glance, this might seem like gatekeeping, but it was nothing of the sort.

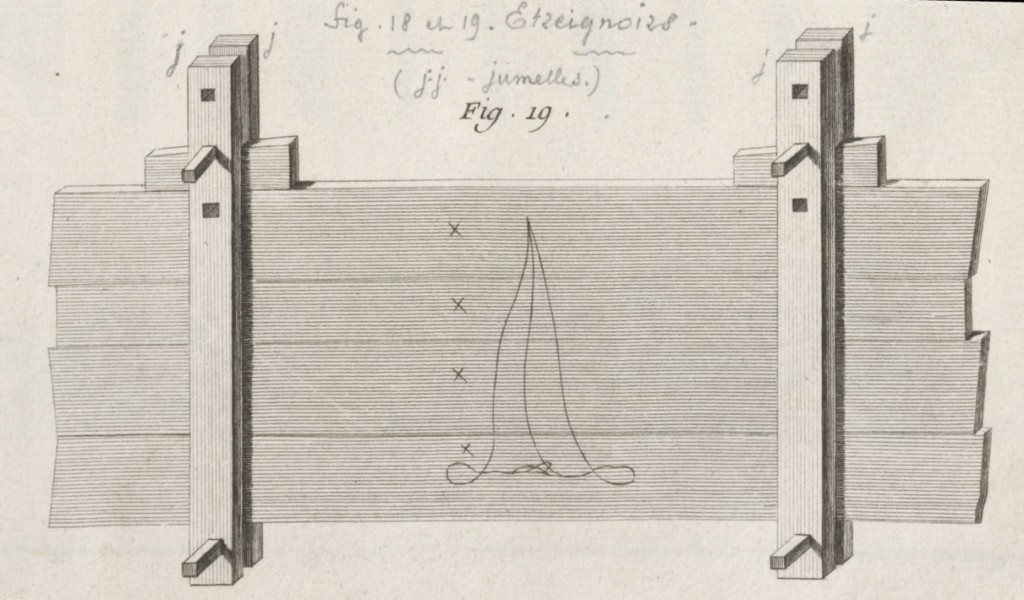

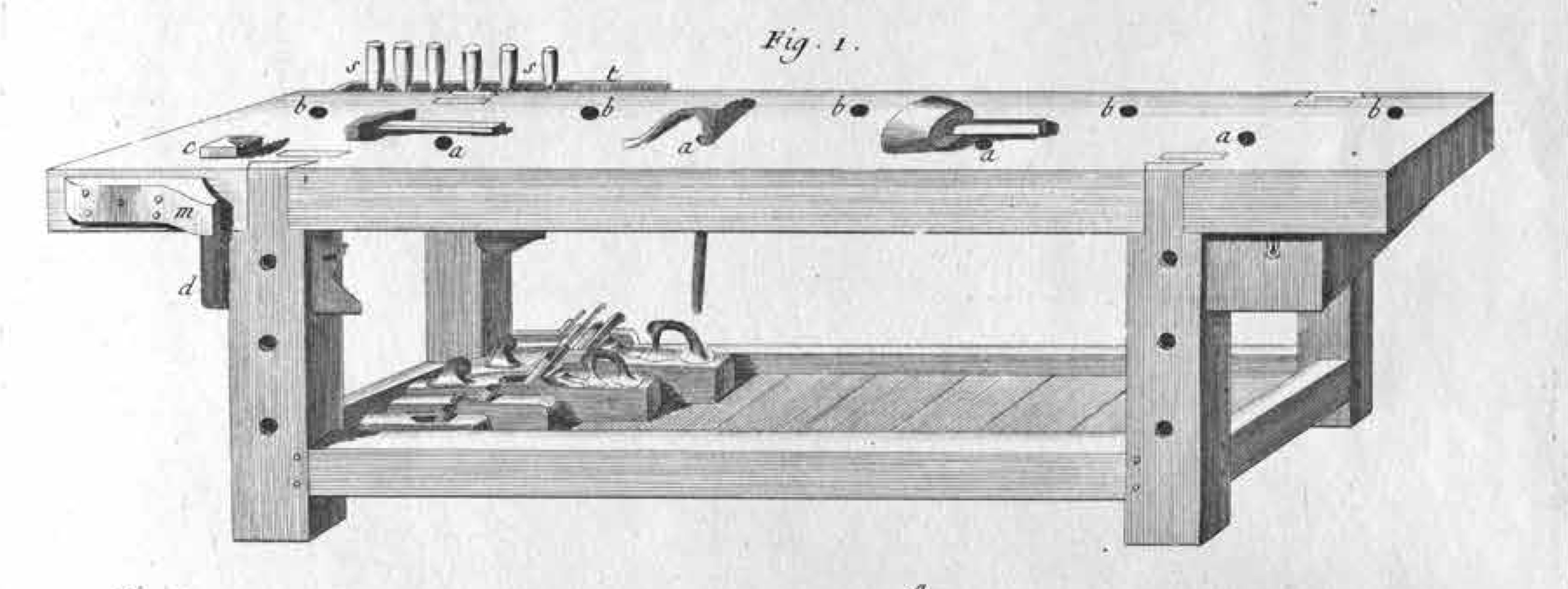

My understaning was, this wasn’t about fashion or elitism. It was about creating a bubble, a moment in time (“1937” according to Roy’s old website). He was not really fixated on this, it was merely a suggestion. But by dressing the part, students stepped out of the modern world and into a historical atmosphere where traditional hand tool woodworking wasn’t just a technique, but a way of life. The clothes weren’t a uniform, they were part of the scenery, like the hand-forged hardware on the workbenches or folks sharpening their tools in the corner.

Roy wasn’t trying to exclude anyone. Quite the opposite: he was inviting them in — into a richer, slower, more thoughtful world, if only for a day. And somehow, when you put on that old chambray shirt and picked up a wooden jointer plane, it became just a little easier to believe you were walking in the footsteps of those who shaped the world hundreds of years before electricity ever hummed in a shop.

Choosing Your Tools and Techniques — It’s Personal

One of the great gifts of woodworking is that it meets you where you are. Some of us love sharpening. Some of us don’t. Some people cut dovetails by hand because they enjoy the quiet focus. Others use a jig on a router table because they want to get on with the next step.

These are personal choices, not moral ones.

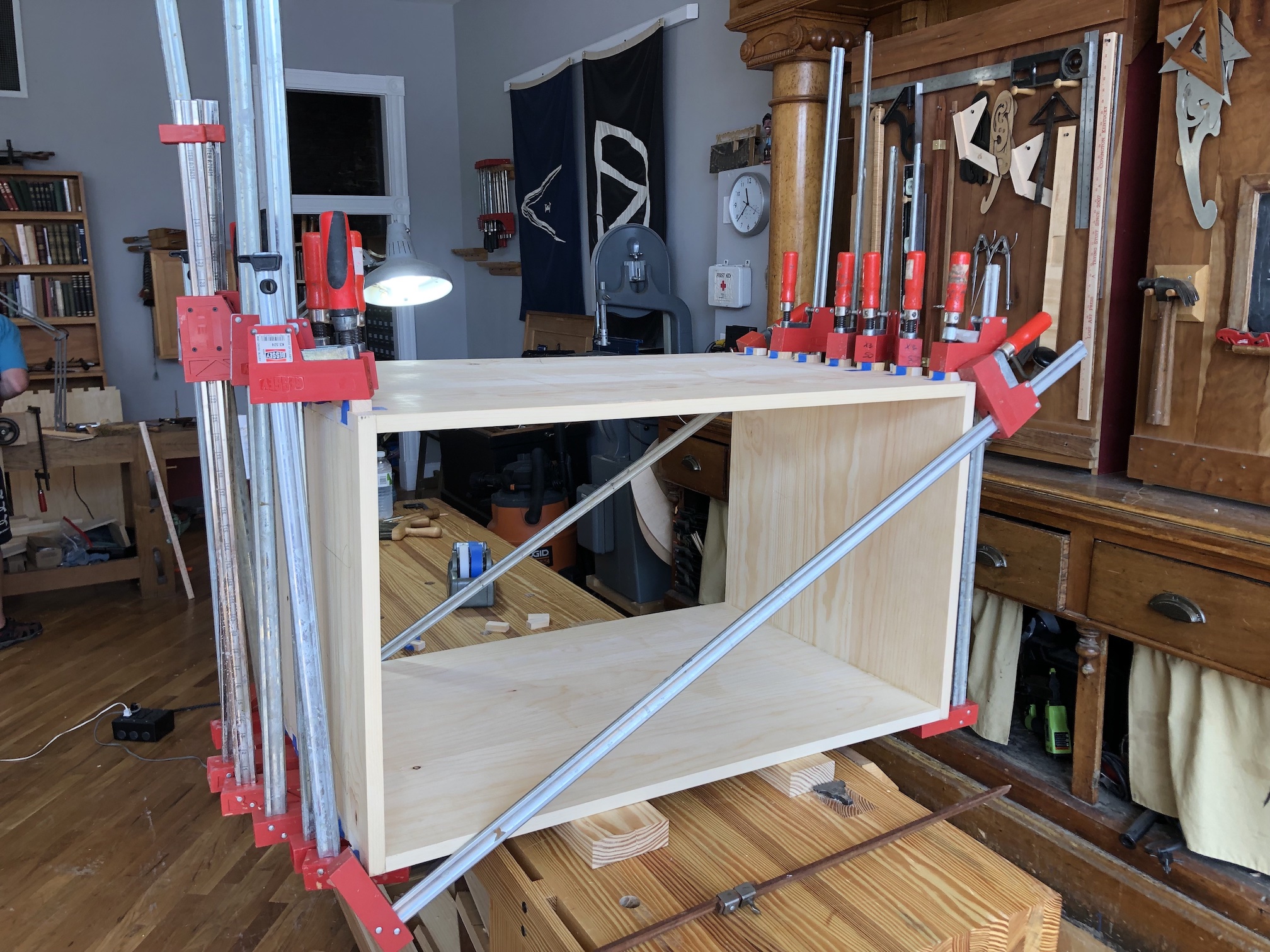

I gravitate toward hand tools not out of purism, but because I enjoy the tactile connection to the work. I like being able to hear the wood talk to me. But I also use a cordless drill. Sometimes I use a bandsaw, drill press or even a table saw (I’m very cautious and respectful of all power tools especially the table saw), and that’s okay too.

Your shop should serve you, not some imagined standard spouted by some self appointed and ego inflated “Master”.

What Really Matters: Utility and Joy

In the end, here’s what really matters:

Does the thing you made do what you needed it to do?

Did you enjoy making it?

If the answer to those two questions is “yes,” and you follow safe practices, then nothing else really matters. Not the brand of tools you used. Not whether the joinery was hand cut. Not whether your sharpening method is “traditional” or your wood species is period correct.

What matters is that you made something that filled a need, either functional or emotional, and you took pleasure in the making.

That’s the heart of it.

So whether you’re flattening boards with a #7 jointer plane or gluing up MDF from the home center, don’t let anyone tell you you’re doing it wrong. The true craft is in the doing. The joy is in the journey. Let your wood chips or sawdust fly!

Let’s support each other, learn from each other, and make things, beautiful, ugly, perfect, imperfect, that speak to us.

Thanks for reading. I’d love to hear what you’re working on, whether it’s with a chisel or a table saw. Drop a comment below and share your project!